Reposted from

Eye on the Amazon.

One might wonder why one of the most clear-cut cases of environmental destruction and criminal corporate acts will be

heard in yet another courtroom twenty-three years after the first legal claims were ever made. The only reason is because when corporations like Chevron are committed to throwing billions of dollars at fighting justice instead of accepting responsibility, they often are able to delay (and thus deny) justice in perpetuity. For the sake of justice everywhere, this must end here and now.

This chapter in the ongoing saga of Chevron's toxic contamination in Ecuador highlights one of the most grievous threats to the notion of justice in the face of crimes committed by corporations anywhere in the world.

There's no good reason why anyone should have to be continuing this fight in Toronto, but Amazon Watch is here today because it's "Day One" of a

critical enforcement trial in Canada to make Chevron finally pay the US $9.5 billion (now closer to US $11 billion with interest) it owes to clean up the biggest oil-related disaster in history which is still polluting the Ecuadorian Amazon today – close to fifty years since drilling first began. We are here alongside our Ecuadorian allies because Chevron has vowed to "fight until hell freezes over and then fight it out on the ice" rather than do the right thing and clean up its mess – a mess it has confessed to creating deliberately in order to squeeze a little more profit out of its operations in the Amazon.

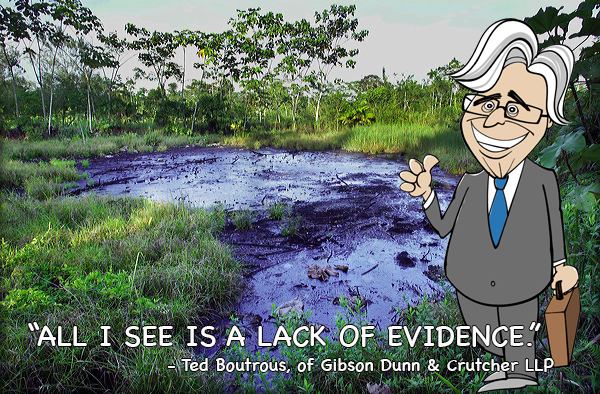

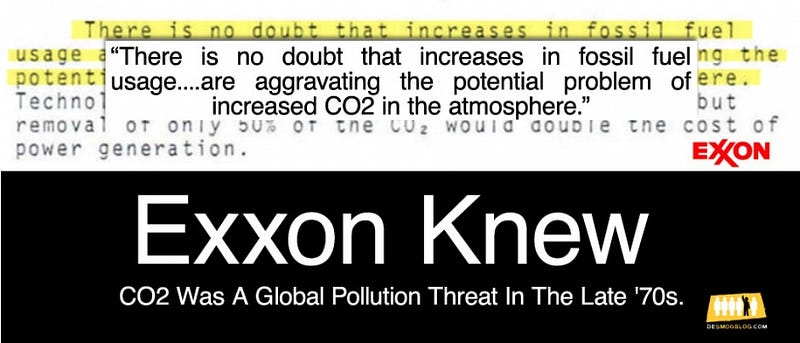

As everyone should know by now, Texaco (now owned by Chevron) admitted to systematically dumping billions of gallons of toxic oil drilling waters into nearly 1,000 open-air pits in the rainforest. Those pits remain today, despite a 1992 agreement Texaco signed with the government of Ecuador to "clean up its share." Turns out that small portion that Texaco incorrectly claimed was "its share" wasn't actually cleaned up (which has been independently verified by many, including the

company's own videos leaked to Amazon Watch by a Chevron whistleblower).

Despite those incontrovertible facts, in recent years Chevron has succeeded (by spending hundreds of millions of its shareholder's money on lawyers and PR firms) in changing the story to one about alleged fraud and malfeasance by what they call "corrupt lawyers" and "unethical environmental groups." There's a perverse logic to this, since when considering that the evidence is so soundly against it in Ecuador, Chevron's management decided it's could only fight on by vilifying its critics in a profoundly bizarre way, claiming it was the "real victim" in the case.

But in Canada that convoluted story becomes a lot more problematic for the oil giant. Here Chevron will attempt to defend itself with the results of its outrageously flawed US SLAPP suit against the massive and damning evidence in the Amazon. They will ask Canada's courts to ignore the company's admission of intentional dumping, the wave of cancers and other health impacts, the indigenous peoples decimated by the contamination, the growing number of environmental and human rights NGOs publicly condemning Chevron for its failure to clean up and transparent tactics to attack its critics, and the reality that three levels of Ecuadorian courts – including its Supreme Court – reviewed the evidence (including Chevron's fraud claims) and unanimously ruled against the company.

Furthermore, Chevron will walk into court today and ask the judge to ignore the laws of his own country and throw out the entire enforcement case based on the findings of a US judge who never went to Ecuador, doesn't understand Spanish, and refused to allow a single piece of evidence in court of the actual contamination in the Amazon. Even according to the appellate decision itself, the US case has no legal relevance in Canada. Regardless, Chevron will demand that the Canadian court accept the word of disgraced former Ecuadorian judge Alberto Guerra, Chevron's star witness,

who admitted to lying in his testimony about a bribe to get a bigger payout from Chevron. Guerra received US $2 million to testify and has been unable to offer any hard evidence of his claims of a ghostwritten verdict, but Chevron still expects the Canadian judge to believe he's credible.

The reality of this week's hearing is as simple as the first case brought against Texaco in 1993. In fact, this week's proceedings are a simple debt collection trial. Common in Canadian law is the basic notion that a party can request to enforce a valid foreign judgment and seek assistance in forcing a debtor to pay up. Meanwhile, Chevron is understandably worried and is

already seeking to sell billions of dollars of Canadian assets, as we have reported before. Chevron also claims that its Canadian assets – the same ones it reports to its shareholders each year – can't be touched because they're not really theirs, something that we expect to hear more about later in the week.

Fortunately, so far the Canadian courts have shown no signs that they are willing to arrogantly dismiss every Ecuadorian court as corrupt and refuse to review the evidence, unlike US Federal Judge Lewis Kaplan and his superiors on the Second Circuit Court of Appeals. Indeed Canada's Supreme Court has already sided unanimously against Chevron and allowed this trial to move forward. We will be here all week, with

support from some of Canada's largest environmental organizations, to observe the hearings and continue to confront Chevron's ongoing lies in its attempt to crush the people brave enough to take on the third largest US corporation.

UPDATE

Chevron's weak argument: Canadian wing is separate from the mothership

When Chevron first stood to defend itself from the

Ecuadorians legal action to

enforce the $9.5 billion verdict to pay for a clean-up, its opening argument couldn't have been more befitting of the oil giant. This is, after all, the company whose lawyers were blasted in US Federal Court last April for suggesting that "it was Texaco" that was responsible in Ecuador and that Chevron is a different company. True to form, Chevron kicked off its opening argument by claiming that Chevron Canada is not the same as Chevron Corp and therefore can't be held liable for Chevron Corp's debts.

Most of the courtroom yawned through a lengthy presentation of all the ways Chevron Canada is different from Chevron Corp – Chevron's lawyers even went so far as to point out that one has headquarters in Canada and the other in the US. That's really their legal argument?

Here's the rub for Chevron: as the lawyer for the Ecuadorians, Alan Lenczner, explained, the court doesn't even need to rule on the issue of "corporate separateness" to decide whether the Ecuadorians can enforce the judgment in Ontario. They only need show only they have a judgment debt from a foreign court. Which they do, of course.

After hours of Chevron attempts to distance itself from Chevron Canada, Lenczner called Chevron out for its same tired tactics. As he forcefully argued, "this company polluted the area [the Ecuadorian Amazon] and then dragged these people through twenty years of litigation! In first instance they sought to bring their case in the US and Chevron said no. Now they are here. This is a commercial court and it should recognize the debt that is owed."

Lenczner also pulled apart Chevron's transparent attempt to show Chevron Canada isn't directly connected to Chevron Corp because there are six subsidiaries between the two; he explained how every one of those entities is simply an investment company and the funds pass directly from one to the other up to Chevron. "Chevron Canada is one of the cash cows that sends money to its parent. It sends $5 billion a year in dividends," he said.

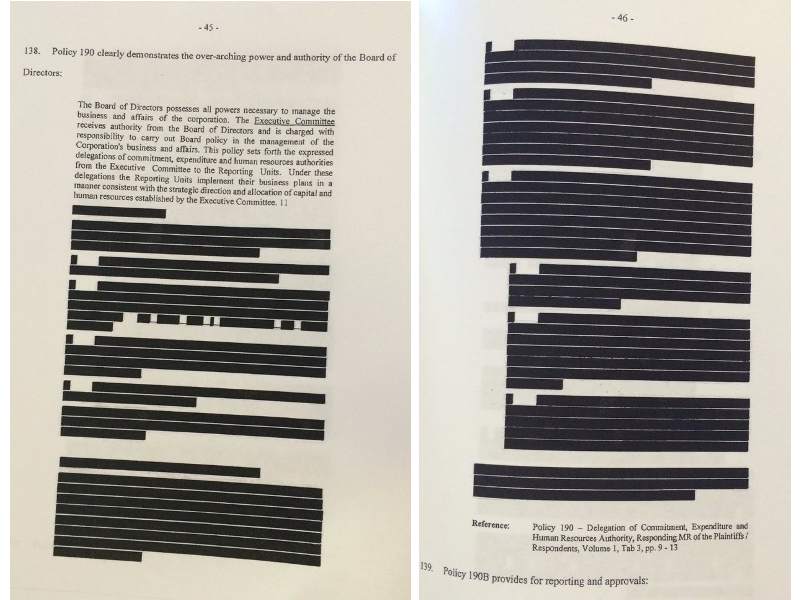

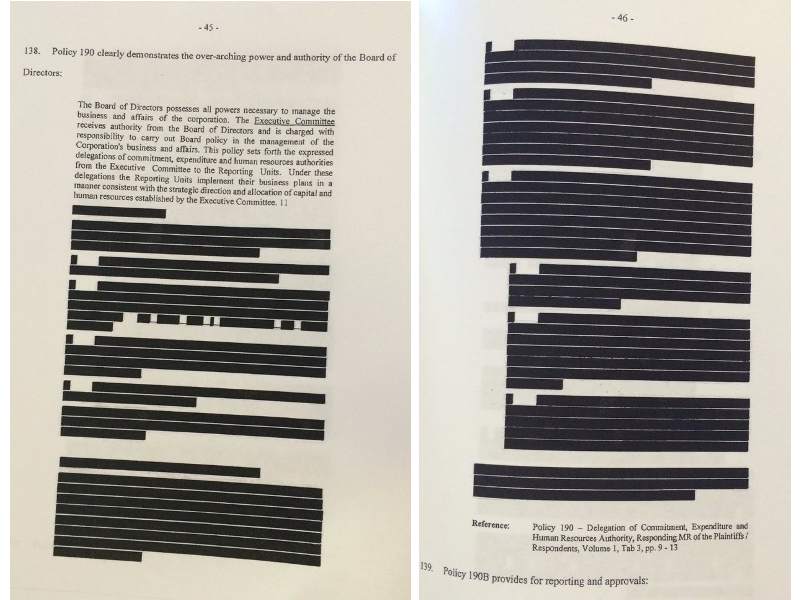

Further demonstrating the corporate oversight Chevron Corp exercises over its Canadian wing, Lenczner highlighted that fact that, per Chevron's own internal policies, every decision of $25 million or over needs to get direct approval from the Vice Chairman at Chevron Corp.

"They can't even drill a new well without concurrence – complete agreement," Lenczner said. “But I am not even 'allowed' to say this, your Honor." Lenczner referred to the fact that as the trial, began the company redacted the public copy of Lenczner's factum to hide all its policies that would show the level of controls over its subsidiaries. Chevron's lawyers were visibly agitated and squirmy as he continued to say things he was "not allowed to say" and declared that the public has a right to know and his brief must be unredacted. Today, both sides will continue to argue over those redactions, but for those of us with years of experience watching Chevron tactics in the courtroom, it's no surprise they want to keep the truth about their practices hidden from view.

UPDATE #2

Chevron's Cash Cow

The Chevron trial in Canadian commercial court continues as 30,000 people from Ecuadorian indigenous and farmer communities seek to enforce their $9.5 billion verdict against Chevron for an environmental clean-up.

The Ecuadorians are using Canada's Foreign Judgment Execution Act in an attempt to gain legal recognition of the Ecuadorian court's judgement against Chevron Corp. and use the assets of Chevron Canada to satisfy it.

Chevron's legal options here are narrow. According to Canadian legal precedent, there are very few defenses that can be raised with respect to recognition and enforcement when preceded by a final judgment like the one from Ecuador (where Chevron fought – and lost – all the way through Ecuador's Supreme Court). So Chevron will not be able to prevail by relying on the same laundry list of recycled arguments it has used to obfuscate what is at its essence a very simple issue of deliberate and widespread contamination by the oil giant.

But with a straight face, Chevron tried one more time.

The company started off the week by dusting off its old "It wasn't me" routine. It has argued before various courts that the Ecuadorians were suing the wrong company; that Texpet (as Texaco was known in Ecuador) is not the same as Texaco; that Texaco is not part of Chevron; that Chevron Corp. doesn't have any assets in Canada because Chevron Corp. and Chevron Canada are not the same company. That's right, shareholders: Chevron and Texaco didn't technically merge, it was a

reverse triangular merger! And the money generated by Chevron Canada doesn't get paid out to your dividends! With arguments like that Chevron, with feigned incredulity, claimed it doesn't know why it's even in the Toronto courtroom. Apparently it ignored this scolding from the U.S. Court of Appeals in New York:

"Chevron Corporation claims, without citation to relevant case law, that it is not bound by the promises made by its predecessors in interest Texaco and ChevronTexaco, Inc. However, in seeking affirmance of the district court's forum non conveniens dismissal, lawyers from ChevronTexaco appeared in this Court and reaffirmed the concessions that Texaco had made in order to secure dismissal of Plaintiffs' complaint. In so doing, ChevronTexaco bound itself to those concessions. In 2005, ChevronTexaco dropped the name "Texaco" and reverted to its original name, Chevron Corporation. There is no indication in the record before us that shortening its name had any effect on ChevronTexaco's legal obligations. Chevron Corporation therefore remains accountable for the promises upon which we and the district court relied in dismissing Plaintiffs' action."

Often, in seeking to hold transnational corporations accountable for environmental crimes and human rights abuses, victims are forced to seek relief from the parent company because the local subsidiary is purposely set up as a limited liability company with no assets, no money, and questionable legal standing. But in this case the Ecuadorians have a judgment against the parent company – Chevron Corp. itself – and seek to fulfil the judgment debt using subsidiary assets.

As a result, all that the attorneys for the communities need to show is a direct relationship between the parent company and the subsidiary. In this case, it is complete dominance.

"Chevron is tied hand and foot to Chevron Canada," said Alan Lenczner, attorney for the plaintiffs to the court. "Chevron Canada is Chevron's cash cow."

Want to see what Chevron internal docs say about its financial relationship to Chevron Canada? So do we.

Want to see what Chevron internal docs say about its financial relationship to Chevron Canada? So do we.

To back up this argument, the Ecuadorians used discovery to obtain copies of internal Chevron documents that expose just how much control Chevron Corp. has over its subsidiaries. But Chevron doesn't want the public to see them. Responsive documents turned over were heavily redacted. Several pages were blacked out entirely. But Mr. Lenczner had seen the unredacted version, and shared the details of them in oral argument with the court.

It turns out that Chevron Corp. is a holding company that doesn't own anything – not even its office buildings. It's essentially a shell company with all of its assets compartmentalized and stored in its subsidiaries, which is clearly an attempt to avoid responsibility in exactly this kind of case.

Chevron Canada is a "7th tier subsidiary" of Chevron Corp. The other six companies in between Chevron Corp. and Chevron Canada are investment companies, with every level being 100% owned by the level above it. Finance flows down the cash cascade from Chevron Corp. to Chevron Canada and returns in dividends.

Apparently Chevron Canada can't do anything on its own. There are no independent directors and the company must get agreement from the higher ups in Chevron Corp. for virtually every decision – from the major to the mundane. Money for off-road tires? Yep, have to go to corporate. Bid on a tar sands oil block in Athabasca? Talk to headquarters. Joining a pipeline consortium? Run it up the chain of command. Signing an office lease? Not without agreement from a Chevron Corp. Vice Chairman.

Maybe the best person to be deposed if this case does go to trial is John Watson, the current Chevron Corp. CEO and Chairman of the Board. He ran Chevron Canada for years, so he must have intimate knowledge about how his corporate veil really works in practice. He also has the unique distinction of orchestrating Chevron's acquisition, err, reverse triangular merger, with Texaco when he was head of mergers and acquisitions before becoming the CEO of Chevron Corp.

Chevron has tried to treat the entire Canadian proceeding as a

first instance case – and then arguing that there's a lack of jurisdiction. This is absurd because the Ecuadorian judgment the communities are seeking to enforce is a final judgment from the country's Supreme Court. It is not a new case. Over ten years it passed through three layers of Ecuadorian courts – trial, appellate, and Supreme courts. The communities are merely seeking to enforce it.

So Chevron cannot re-litigate the entire case, and it cannot present defenses that have already been heard in the original proceedings. And Chevron has certainly been heard. According to the trial record, there are some 216,692 pages of evidence, 100 expert reports, 56 official visits to toxic sites. Chevron participated at every level. It brought 1,000 motions. There were 20,000 pages presented to the appeals court, and 10,000 more to the national Supreme Court.

Chevron's tactics have always been to deny and delay, hoping to drag out the proceedings as long as possible to avoid paying and hope that the communities will give up, run out of money, or worse. The company is literally trying to delay justice in this case until all of the original plaintiffs are dead. The company's counsel famously said, "We'll fight this until hell freezes over, and then we'll fight it out on the ice."

Well Chevron better lace up its skates, because they may get a hearing in Canada on exactly what they don't want to talk about: undeniable contamination in Ecuador and concocted claims of bribery and ghostwriting.

When counsel for the communities began to talk about the trial record in Ecuador and the 16.8 million gallons of oil spilled, 15 billion gallons of toxic waste water dumped, and over 1,000 oil pits that stain the rainforest floor, Chevron lawyers jumped from their seats.

Chevron tried to cut off any mention of their contamination. But unlike Judge Kaplan in New York, who forbade any talk of it and rarely let lawyers for the communities finish a sentence, Judge Hainey allowed it. The courtroom heard the criminal shortcuts Chevron took, like dumping waste instead of re-injecting it deep into the ground as was standard industry practice and building pits with no lining that allowed heavy metals and carcinogens to overflow into the forest and leach into groundwater.

"It's disastrous. A number of people die every year," Lenczner said.

Mr. Lenczner closed the day arguing for a truncated trial specifically on Chevron's claims of bribery and ghostwriting.

"Chevron concocted a sordid – and untrue – tale of bribery and ghostwriting," argued Lenczner. "But Chevron's star witness in that case – a corrupt ex-judge who Chevron paid over $2 million and coached for 52 days to testify, has recanted his testimony in a different proceeding."

"Let's have a trial on that. Bring it on!"

On Chevron claims that the communities and lawyer ghostwrote the judgment, Lenczner exclaimed, "Let's have a trial on that, too," citing forensic evidence that proves the judge was written by him alone on his computer.

While Chevron's back is up against the wall in Canada, you wouldn't necessarily know it by the media coverage in the U.S. Reporters who have covered the saga with incredible, pro-Chevron bias have been quick to write off the Ecuadorians.

Those "journalists" are conveniently absent in the courtroom up here, nowhere to be found when the tide turns against the company.

The Ecuadorians are still standing, and may be closer to justice than ever. And if they can use Chevron Canada's assets to pay for a clean up, it will be a victory for communities around the world who seek to put an end to corporate impunity.

Want to see what Chevron internal docs say about its financial relationship to Chevron Canada? So do we.

Want to see what Chevron internal docs say about its financial relationship to Chevron Canada? So do we.