Looking back on Chevron’s retaliatory RICO trial, it is

clear that the oil company’s lawyers were so terrified of some of their own

witnesses that they literally ordered them to stay away from court.

Remember Douglas Beltman and Ann Maest, the scientific consultants for the rainforest indigenous and farmer communities in Ecuador that were devastated by Chevron’s toxic dumping? Beltman and Maest helped the communities win their historic judgment against Chevron in Ecuador’s courts. The judgment recently was affirmed by Ecuador's Supreme Court.

Several months ago, desperate to evade a court order that it clean up its toxic mess, Chevron launched a public relations offensive in the U.S. that claimed Beltman and Maest had “disavowed” their work for the communities harmed by Chevron's pollution. In opening arguments in the RICO case in October, Chevron lawyer Randy Mastro touted Beltman and Maest as key witnesses against New York human rights lawyer Steven Donziger, the company’s principal target.

So why did Mastro and his team of 114 lawyers at Gibson Dunn decide to bail on Beltman and Maest? And what does the sudden disappearance of these witnesses tell us about the validity of Chevron’s RICO case?

Mastro knew that under cross-examination Beltman and Maest almost certainly would have delivered damning testimony against Chevron. As far as the case is concerned, Chevron’s failure to call these witnesses underscores yet again how weak the company’s evidence is -- which is why Chevron dropped damages claims on the eve of trial to avoid a jury of impartial fact finders.

The most important of Chevron’s witness desaparecidos is Beltman, a nationally-acclaimed scientist who in 2009 appeared in a 60 Minutes segment condemning the company’s decades-long record of toxic dumping in Ecuador.

Last Spring, Chevron secured an affidavit from Beltman which the oil giant claimed shows he had “disavowed” his work for the communities and recanted his comments to 60 Minutes. In April 2012, with much fanfare, Chevron issued a corporate press release trumpeting Beltman’s supposed retreat. As usual, the company failed to disclose key facts.

One of those facts is that Chevron had aimed a veritable bazooka at Beltman’s head to get him to sign the affidavit. The company had named Beltman as a RICO defendant and threatened to bankrupt Stratus if Beltman didn’t capitulate. Chevron sent a series of shakedown letters to clients of Stratus, falsely claiming that Beltman had been found to have committed fraud.

The reality is that Beltman never changed his opinion that Chevron is responsible for massive and life-threatening toxic contamination in Ecuador. Read this blog for more on the back story of Chevron's campaign of economic extortion to silence witnesses. Citing this evidence, 60 Minutes flat out refused Chevron's bogus demand that it issue a "correction" to the original story.

In exchange for Beltman’s affidavit -- clearly written by Chevron lawyers -- Chevron dropped Beltman and Stratus as defendants in the RICO action. At the same time, Stratus agreed to drop a lawsuit against Chevron where the consultancy had accused the oil giant of engaging in a “an extrajudicial campaign of malicious defamation.” Read the Stratus lawsuit to get a sense of how vicious Chevron’s strategy had become.

The reason Mastro chickened out with his key witnesses is pretty simple. Beltman (and Maest) only “disavowed” their work on a single technical report that the Ecuador court excluded as evidence. Neither were involved in the more than 100 other technical reports that the Ecuador court relied on to find Chevron liable. In other words, the affidavits were a big non-event in terms of the trial.

They were a nice illustration of Chevron's venal tactics. Chevron did not want the court nor journalists to hear Beltman’s truthful testimony, so Mastro squelched it. Beltman’s real view of Chevron’s bad acts can be seen in this power point presentation he prepared in 2010. Or read his sworn deposition testimony from 2011.

Nearly the exact same thing happened with another of Chevron’s favorite witnesses, the American technical expert Dr. Charles Calmbacher. On the first day of the RICO trial, Mastro said Calmbacher was going to testify. But he also was a big no-show.

The reason: Calmbacher lied in a pre-trial deposition about disavowing his own court-ordered technical reports prepared for the communities. In fact, the evidence shows that Calmbacher found extensive toxic contamination at the former Chevron sites he inspected and he turned on the communities out of spite over a fee dispute. See pp. 53-55 of Donziger’s sworn witness statement for the documentation.

Another of Chevron's disappearing witnesses, the Ecuadorian technical expert Fernando Reyes, signed a sworn affidavit earlier this year that was trumpeted by the company's PR flaks. But in his pre-trial deposition, Reyes undermined a key plank of Chevron’s fake narrative by saying that it was normal in Ecuador for court-appointed experts to work closely with the parties. So Mastro, who ran the case like a public relations campaign, silenced him too.

Other Chevron witnesses who were never called to court also include two of Donziger’s former associates, Laura Garr and Andrew Woods. What happened?

Chevron stood nothing to gain once it got the public relations hit in opening arguments of falsely claiming the pair had turned on Donziger. You can bet that if called to the witness stand, both would have lauded Donziger for his commitment to his clients even if they griped on occasion about his demanding management style. So they were told to stay away.

Chevron always has used the RICO case to pre-package witness affidavits drafted by its own lawyers and then peddle them to Judge Kaplan and the media. In fact, these ghostwritten affidavits were central only to Chevron’s public relations strategy to distract attention from its environmental crimes in Ecuador by “demonizing” Donziger and his clients.

Once the trial was on and the rubber had to meet the road, Mastro shuddered at the thought that any of the pre-packaged testimony might veer off-script. It's also why he abruptly aborted his cross-examination of Donziger, who was making the self-annointed former "mob prosecutor" look a bumbling fool who was lost in the weeds and could not frame a question properly.

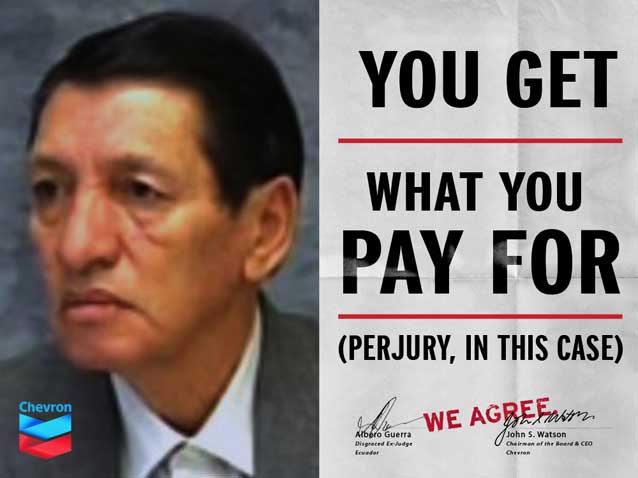

Several months ago, a reporter at American Lawyer (Michael Goldhaber) declared the entire Ecuador case over after former Ecuador Judge Alberto Guerra signed a sworn affidavit claiming that the plaintiffs had bribed a sitting judge. Almost overnight, based on a Chevron-drafted affidavit, Guerra became Godhaber’s new media sensation.

Unlike Beltman and Maest, Chevron had no choice but to call Guerra to the stand. His claims were just too important.

Under cross-examination, Guerra wilted. He admitted he was a criminal who had fixed dozens of cases and that Chevron was paying him (in violation of federal law) vast sums of money for favorable testimony. Guerra’s show trial performance was a hilarious illustration of just how weak Chevron’s case really is. Read pp. 31-41 of this post-trial brief to understand how Guerra’s testimony is riddled with lies, inconsistencies, and constantly changing stories.

Guerra played Chevron for a fool, and Chevron played Goldhaber for a fool. And Mastro, a leader of a practice group that has been consistently nailed by courts for engaging in unethical litigation practices, keeps Chevron’s false hope alive while billing CEO John Watson an estimated $400 million annually for services that have caused nothing but more and more risk for the company’s shareholders.

Chevron is now left with precious little of long-term value for its huge investment in the RICO case. It still has trial judge Lewis A. Kaplan as the sole “Decider” of the case (at least before the appellate courts weigh in). But Kaplan is seriously lacking in credibility due to his xenophobic comments toward the Ecuadorians, his biased promotion of Chevron’s cause, and his grandiose desire to serve as a de facto appellate panel for the Ecuadorian judiciary. Kaplan's expected decision in favor of Chevron will be laughed at by enforcement courts around the world and has little chance of surviving appeal in the United States.

Kaplan’s hyperactive efforts to jump through tighter and tighter hoops to favor Chevron has been nothing short of astonishing to the world legal community. See this brief from international legal scholars, this brief from New York University law professor Bert Neuborne, and this post-trial brief in the RICO case to get a sense of the man’s intellectual dishonesty and sheer arrogance.

John Keker, known as one of the most formidable trial lawyers in the nation who counts Google among his many clients, said in his recent motion to withdraw that Kaplan had allowed the RICO case to degenerate into a “Dickensian farce” due to his mismanagement of the docket and his “implacable hostility” toward Donziger, who has battled on behalf of the rainforest communities for two decades.

Chevron has played a cynical game of carrot & stick, manipulating witnesses with exorbitant payments (Guerra) or ferocious personal and economic pressure (Beltman and Maest). Team Mastro and the Lords running Chevron would never get away with it if the case were before a judge who wasn’t clearly biased against the Ecuadorians and Donziger.

All of Chevron’s testigos desaparecid

Remember Douglas Beltman and Ann Maest, the scientific consultants for the rainforest indigenous and farmer communities in Ecuador that were devastated by Chevron’s toxic dumping? Beltman and Maest helped the communities win their historic judgment against Chevron in Ecuador’s courts. The judgment recently was affirmed by Ecuador's Supreme Court.

Several months ago, desperate to evade a court order that it clean up its toxic mess, Chevron launched a public relations offensive in the U.S. that claimed Beltman and Maest had “disavowed” their work for the communities harmed by Chevron's pollution. In opening arguments in the RICO case in October, Chevron lawyer Randy Mastro touted Beltman and Maest as key witnesses against New York human rights lawyer Steven Donziger, the company’s principal target.

So why did Mastro and his team of 114 lawyers at Gibson Dunn decide to bail on Beltman and Maest? And what does the sudden disappearance of these witnesses tell us about the validity of Chevron’s RICO case?

Mastro knew that under cross-examination Beltman and Maest almost certainly would have delivered damning testimony against Chevron. As far as the case is concerned, Chevron’s failure to call these witnesses underscores yet again how weak the company’s evidence is -- which is why Chevron dropped damages claims on the eve of trial to avoid a jury of impartial fact finders.

The most important of Chevron’s witness desaparecidos is Beltman, a nationally-acclaimed scientist who in 2009 appeared in a 60 Minutes segment condemning the company’s decades-long record of toxic dumping in Ecuador.

Last Spring, Chevron secured an affidavit from Beltman which the oil giant claimed shows he had “disavowed” his work for the communities and recanted his comments to 60 Minutes. In April 2012, with much fanfare, Chevron issued a corporate press release trumpeting Beltman’s supposed retreat. As usual, the company failed to disclose key facts.

One of those facts is that Chevron had aimed a veritable bazooka at Beltman’s head to get him to sign the affidavit. The company had named Beltman as a RICO defendant and threatened to bankrupt Stratus if Beltman didn’t capitulate. Chevron sent a series of shakedown letters to clients of Stratus, falsely claiming that Beltman had been found to have committed fraud.

The reality is that Beltman never changed his opinion that Chevron is responsible for massive and life-threatening toxic contamination in Ecuador. Read this blog for more on the back story of Chevron's campaign of economic extortion to silence witnesses. Citing this evidence, 60 Minutes flat out refused Chevron's bogus demand that it issue a "correction" to the original story.

In exchange for Beltman’s affidavit -- clearly written by Chevron lawyers -- Chevron dropped Beltman and Stratus as defendants in the RICO action. At the same time, Stratus agreed to drop a lawsuit against Chevron where the consultancy had accused the oil giant of engaging in a “an extrajudicial campaign of malicious defamation.” Read the Stratus lawsuit to get a sense of how vicious Chevron’s strategy had become.

The reason Mastro chickened out with his key witnesses is pretty simple. Beltman (and Maest) only “disavowed” their work on a single technical report that the Ecuador court excluded as evidence. Neither were involved in the more than 100 other technical reports that the Ecuador court relied on to find Chevron liable. In other words, the affidavits were a big non-event in terms of the trial.

They were a nice illustration of Chevron's venal tactics. Chevron did not want the court nor journalists to hear Beltman’s truthful testimony, so Mastro squelched it. Beltman’s real view of Chevron’s bad acts can be seen in this power point presentation he prepared in 2010. Or read his sworn deposition testimony from 2011.

Nearly the exact same thing happened with another of Chevron’s favorite witnesses, the American technical expert Dr. Charles Calmbacher. On the first day of the RICO trial, Mastro said Calmbacher was going to testify. But he also was a big no-show.

The reason: Calmbacher lied in a pre-trial deposition about disavowing his own court-ordered technical reports prepared for the communities. In fact, the evidence shows that Calmbacher found extensive toxic contamination at the former Chevron sites he inspected and he turned on the communities out of spite over a fee dispute. See pp. 53-55 of Donziger’s sworn witness statement for the documentation.

Another of Chevron's disappearing witnesses, the Ecuadorian technical expert Fernando Reyes, signed a sworn affidavit earlier this year that was trumpeted by the company's PR flaks. But in his pre-trial deposition, Reyes undermined a key plank of Chevron’s fake narrative by saying that it was normal in Ecuador for court-appointed experts to work closely with the parties. So Mastro, who ran the case like a public relations campaign, silenced him too.

Other Chevron witnesses who were never called to court also include two of Donziger’s former associates, Laura Garr and Andrew Woods. What happened?

Chevron stood nothing to gain once it got the public relations hit in opening arguments of falsely claiming the pair had turned on Donziger. You can bet that if called to the witness stand, both would have lauded Donziger for his commitment to his clients even if they griped on occasion about his demanding management style. So they were told to stay away.

Chevron always has used the RICO case to pre-package witness affidavits drafted by its own lawyers and then peddle them to Judge Kaplan and the media. In fact, these ghostwritten affidavits were central only to Chevron’s public relations strategy to distract attention from its environmental crimes in Ecuador by “demonizing” Donziger and his clients.

Once the trial was on and the rubber had to meet the road, Mastro shuddered at the thought that any of the pre-packaged testimony might veer off-script. It's also why he abruptly aborted his cross-examination of Donziger, who was making the self-annointed former "mob prosecutor" look a bumbling fool who was lost in the weeds and could not frame a question properly.

Several months ago, a reporter at American Lawyer (Michael Goldhaber) declared the entire Ecuador case over after former Ecuador Judge Alberto Guerra signed a sworn affidavit claiming that the plaintiffs had bribed a sitting judge. Almost overnight, based on a Chevron-drafted affidavit, Guerra became Godhaber’s new media sensation.

Unlike Beltman and Maest, Chevron had no choice but to call Guerra to the stand. His claims were just too important.

Under cross-examination, Guerra wilted. He admitted he was a criminal who had fixed dozens of cases and that Chevron was paying him (in violation of federal law) vast sums of money for favorable testimony. Guerra’s show trial performance was a hilarious illustration of just how weak Chevron’s case really is. Read pp. 31-41 of this post-trial brief to understand how Guerra’s testimony is riddled with lies, inconsistencies, and constantly changing stories.

Guerra played Chevron for a fool, and Chevron played Goldhaber for a fool. And Mastro, a leader of a practice group that has been consistently nailed by courts for engaging in unethical litigation practices, keeps Chevron’s false hope alive while billing CEO John Watson an estimated $400 million annually for services that have caused nothing but more and more risk for the company’s shareholders.

Chevron is now left with precious little of long-term value for its huge investment in the RICO case. It still has trial judge Lewis A. Kaplan as the sole “Decider” of the case (at least before the appellate courts weigh in). But Kaplan is seriously lacking in credibility due to his xenophobic comments toward the Ecuadorians, his biased promotion of Chevron’s cause, and his grandiose desire to serve as a de facto appellate panel for the Ecuadorian judiciary. Kaplan's expected decision in favor of Chevron will be laughed at by enforcement courts around the world and has little chance of surviving appeal in the United States.

Kaplan’s hyperactive efforts to jump through tighter and tighter hoops to favor Chevron has been nothing short of astonishing to the world legal community. See this brief from international legal scholars, this brief from New York University law professor Bert Neuborne, and this post-trial brief in the RICO case to get a sense of the man’s intellectual dishonesty and sheer arrogance.

John Keker, known as one of the most formidable trial lawyers in the nation who counts Google among his many clients, said in his recent motion to withdraw that Kaplan had allowed the RICO case to degenerate into a “Dickensian farce” due to his mismanagement of the docket and his “implacable hostility” toward Donziger, who has battled on behalf of the rainforest communities for two decades.

Chevron has played a cynical game of carrot & stick, manipulating witnesses with exorbitant payments (Guerra) or ferocious personal and economic pressure (Beltman and Maest). Team Mastro and the Lords running Chevron would never get away with it if the case were before a judge who wasn’t clearly biased against the Ecuadorians and Donziger.

All of Chevron’s testigos desaparecid